Method and reading – Reflections on Confucius and Chinese philosophy (I)

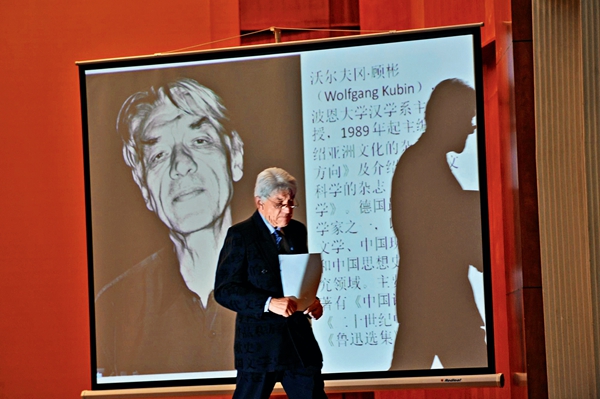

- By Wolfgang Kubin

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail China Today, October 12, 2017

E-mail China Today, October 12, 2017

There are some scholars who claim Chinese philosophy isn't a genuine philosophy, and if it is, they say, it is either too simple or too hard to understand. You will hear similar opinions not only in Europe, but also in China.

In this article, I don't want to examine whether cases like these are only matters of opinion or fact. Instead, I want to highlight the problematic nature of the art of reading difficult Chinese texts. How do we read a Chinese text which doesn't really speak to us innately?

|

|

|

Confucius. |

As is well known in modern hermeneutics, a work that doesn't speak to us is a dead work. Nonetheless, we also know that something we are not yet ready to comprehend or appreciate today might gain our fullest sympathy and attention tomorrow. How is this possible? And what exactly was it that happened to us in such cases between these two incidents in our life?

Let me use myself as an example and thereby reiterate. Due to my early readings of Hegel in Vienna (1968), the words of my first Chinese teacher in Muenster (1969), and my university years during the "cultural revolution" in Beijing (1974-75), I was not at all interested in Confucius (551-479 BC). He appeared to me as boring, trivial and, in comparison to Greek philosophy, which I favored at that time, anything but philosophic.

Why is it then that I like to read Confucian Analects (Lunyu) today and often recite the words of the master, and even defend them, as a response to certain negative developments in Western modernity?

It all has to do with a certain primal experience. In May 1999, I was doing research on Chinese aesthetics. I bought a German translation of the French book In Praise of Blandness, Proceeding from Chinese Thought, and Aesthetics by François Jullien. It opens more or less with the close revision of an inconspicuous passage from Lunyu.

|

|

|

Kubin is a renowned sinologist, poet, and educator. |

In order to spare the readers the impression that he looks at Confucius with a lack of philosophical expertise, Jullien right from the beginning points out the true character of the essence of Chinese culture as he sees it: Something that lies in the middle and appears unimportant at first glance, but which is in fact truly essential.

Whoever takes Hegel's statement of the Lunyu as being trivial seriously should first properly study the Chinese spirit before further debate, as the Chinese spirit defines itself quite differently from ours, namely through its withdrawal from the visible and the structured.

Philosophy and Death

Chinese people are quite right to be afraid of everything designed and modeled, because all that is designed and well-formed confines us to something specific. As the formed and defined version of myself, I am only what I reveal as my shaped self. This self is reduced to certain specific characteristics, but no longer implies the countless number of all possible options as a whole. That is, for instance, why fashion plays such an important role in the Western world, as it allows people to design and define themselves in a very individual way.

|

|

|

|

|

Confucian Analects is one of the most translated Chinese classics. |

On the other side, something unshaped and shapeless is limited only to itself and its potential, but without being perceptible as something special. Thus, from outer appearances it could be many things; however, it prefers to be everything possible in its inner self.

According to Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770-1831) a human being should in general (objectively) be what he is also for himself (subjectively), which means, a person should define himself by what he feels deep inside as well as by his outer appearance, thus resolving the dichotomy of being.

As a consequence of this thought, the concept of self realization appears as a new terminus in Hegel's works from 1816 onwards, and becomes a whole new scheme.

This scheme, however, differs significantly from the Chinese concept of "xiushen." This binominal, which can be translated as "cultivating of one's moral character," is central to Confucianism. Originally, "xiushen" meant the cleansing of all evil in river waters. Confucius regards this concept as a basis for personality development.

According to the classical work The Great Learning, one becomes a person by placing the act of physical cleansing in the context of the empire under heaven, the (vassal) state and the family.

How much a cosmological concept like this takes away from a single person what is a part of his individuality, in the view of the Occidental culture, becomes visible through a later key phrase from the Song Dynasty (960-1279): "Erase human desires and apply the heavenly principles." This phrase goes further than the former requirement of Confucius, by stating that a human being has to "overcome itself, to reinstate the social norms, the rite."

In all the cases named, what one gains is not one's very own unique form, but the form of being itself, the form of everybody and everything. In this way I am indistinguishable from other humans by my outer appearance. Instead I carry the reason for everything within my inner self. This is also why heaven, earth, and humans can be understood as an internal-worldly trinity.

This idea also explains why the former Chinese philosophy remained unspoken. Words form a text, and in this way narrow it down to a few possibilities. Plenty of words might seem to clarify a statement, but in fact, they muddy it.

In the case of Confucius we have to mentally fill in further thoughts between the Chinese characters and by doing so upgrade the unspoken statements to something philosophical and eloquent.

For instance, let us take a closer look at the following example from Lunyu (IV. 8):

The Master said, "If a man in the morning hears the right way, he may die in the evening without regret."

What does Confucius mean by this statement? From the mouth of Socrates (470-399 BC) we are familiar with the idea that philosophizing means to learn to die. So why not take a detour via Socrates to understand his Chinese peer?

From the European perspective, we might as well ask: Why can a man, who hears about the right way in the morning, not die by noon? Whoever raises questions like this and thereby complements a minimalist saying, will truly start to philosophize. As a consequence, death will become an object of his very own thoughts, just like it became one in the mind of Socrates.

The French philosopher François Jullien has complemented another short and well known passage of the Confucian Analects in this style, which also deals with the subject of death:

The Duke of She asked Zilu about Confucius, but Zilu did not answer him. The Master said: "Why didn't you say to him, ‘he is simply a man, who in his eager pursuit of knowledge forgets his food, who in the joy of its attainment forgets all his sorrows, and who does not perceive that old age is coming on?'"

Zilu's silence is characteristic, because a statement about the Master would have inevitably defined him as a certain something and singled him out as something in particular. However, Confucius himself does not seem to know difficulties like these. He talks about himself in dual images, which make clear what is important to him and what not. The images of eager pursuit and food, joy and sorrow, perception and age contrast each other.

However, we do not know what exactly it is that the Master is eagerly pursuing or feels joy about. Here, like in many other passages in the Analects, there is no clear object following the sentence's verb. Only the last verb "perceive" reveals an object: the coming on of age. As this verb is negated, the content of self-characterization seems to reveal a kind of calmness in the Master Confucius. The search will only end after death, which, however, the Master doesn't seem to fear at all.

What we deal with here is a phenomenon, an exercise, which plays an important role equally in Chinese and Western philosophy. However, this parallelism hasn't been paid much attention to up to now.

Go to Forum >>0 Comment(s)