Paintings to scale a treasured traditional art form

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail China Daily, August 18, 2020

E-mail China Daily, August 18, 2020

Anglers are likely to recount "big fish" stories about herculean battles with silver-scaled kraken. These usually end with the declaration, "It was definitely at least this big!", as they exaggeratedly gesticulate with their hands to indicate the vastly overstated length of their former aquatic nemesis.

It was probably much easier to persuade people that these tales were true before the age of camera-laden smartphones.

However, even before the invention of photography itself, avid anglers around the world came up with inventive ways to prove the legitimacy of, and record, the outstanding fish they managed to land. While those in the West opted for things like fish taxidermy, in China a different method was used to, literally, mark an impressive catch-one that has since evolved into a traditional art form.

The method is called yuta, or fish printing. People apply paint to the fish and press it on paper to record its exact shape and size, and such details as the texture of its scales, fins and tail.

Yu Qinyuan, a native of Gaomi, a county-level city of Weifang, Shandong province, has been a leading figure in inheriting, practicing and promoting the art form.

The 56-year-old was first exposed to the practice as a child.

"I grew up with my grandparents, a scholarly family, who knew the basic fish-printing techniques. When they caught a big fish, they'd print it and frame it as a memento," he recalls.

Yu has been practicing fish printing full time for 10 years. During that time, he has learned from masters from around the country and developed his own systematic approach to the art form.

The uniqueness of fish printing, Yu says, lies in that it is able to precisely capture the details of the fish species. "Each fish scale has its distinctive texture, like a person's fingerprint. The texture cannot be drawn by even the most perceptive painter but is clearly visible when rubbed onto the paper."

He says that a fundamental rule of fish printing is to not use a pen or brush to add any details to the fish. The only exception to the rule is the eyes, which require a great painting technique and often take longer than the printing process.

The origin of fish printing remains unclear.

According to Yu, there is no written record of the art form in historical records, and no ancient works have been found.

But experts believe that the art form might date back to ancient China, as the techniques resemble that of stone rubbings from the Song Dynasty (960-1279). For instance, both art forms use a dabber.

The art form is now known best in Japan as gyotaku, meaning fish rubbing. In China, a small group of practitioners are working to promote the art form.

Yu estimates that fewer than 1,000 people in the country have mastered the skill.

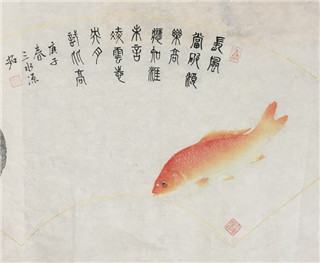

"The Chinese style of fish printing has influences from traditional Chinese painting. Upon completing the printing, usually we would adorn it with drawings of plants and landscapes, calligraphy and also stamps and seals," Yu says.

The Chinese aesthetics are also reflected in the color choices.

While most of the time the artists would select colors to create the original shades of the fish, works commissioned by clients would often use red, as many consider the red koi fish to be auspicious.

Yu is currently working on a 20-meter scroll that incorporates 22 varieties of fish that inhabit Shandong's Weihe River.

Yu led the successful effort to include fish printing on Gaomi's intangible cultural heritage list and the equivalent list of Weifang city this June.

"To be honest, fish printing does not have a standardized system like Chinese watercolors or calligraphy. There are only a handful of practitioners around the country. So each year we will meet up a few times to discuss the techniques, tackle problems together, learn and progress," Yu says.

Yu now has his own studio in Gaomi that aims to promote fish printing. He occasionally hosts short-term training courses in Beijing. So far, more than 100 people have learned the skill from him, either in one of these courses or at his studio.

Yu considers Yan Beiyu one of his best students. She has attended four of his training sessions.

Her interest started in 2018, when she enrolled her 4-year-old daughter on the course as she thought it would be a good approach to introducing children to traditional art. She did not expect to develop an interest in the subject herself.

Yan took the next three sessions by herself and went back to teach her daughter. Now, the entire family practices the skill.

"Yu's teaching method is very detailed and approachable. It's easy for people of all ages to understand and master. He also explains a lot about the origins of the genre and discusses the future of fish printing, and what we can do to promote the art form. It really is a traditional art form suitable for all ages," Yan says.

Go to Forum >>0 Comment(s)