| Home / Education / News | Tools: Save | Print | E-mail | Most Read |

| Digging for the Truth |

| Adjust font size: |

"Do you want to die?" a man roared.

Terrified, Cao scuttled out of the mineshaft. A helpful minder gave him a ride to another nearby coal mine, and from there, he jogged a dozen kilometers to a schoolmate's home. But even after this close call, he returned to Ningxiang County of Central China's This incident wasn't the first in which Cao and the other university students on his research team had been threatened. But in the face of such intimidation, this team managed to defy coal mine managers' threats, cross cultural barriers between them and miners and overcome their own parents' concerns for their safety to produce a research report examining coal miners' awareness of occupational health and safety. The report by the students in The fieldwork was an eye-opener for the 10 undergraduate students from different colleges of

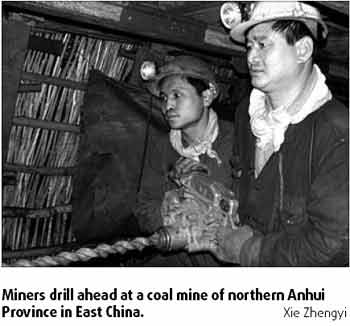

In March 2005, two freshmen, However, this first attempt flopped. Only a few workers returned the surveys, some with every item marked "yes" and others with every item marked "no". When asking coal miners "Do you get frightened in a cinema", or, "Do you feel uncomfortable in a fast car", the students were often asked what a cinema or a car was. Three more students, including a young woman who had grown up in a coal mining community and spoke the miners' dialect, joined the team for a second survey conducted in the city of In all, the group carried out eight surveys from March 2005 to August 2006, visiting more than 30 mines. More than 500 miners throughout Students discovered that offering the miners cigarettes and betel nut helped break the ice. And they also found that if they could win the trust of team leaders, others would be more inclined to cooperate. Gradually, they learned about the miners' living and working conditions, and attitudes. Some of the findings shocked them. For example, they learned that many miners took accidents for granted. "It's inevitable for us to be injured or even die," one said. "It's just a question of who and how many will die at a given time. After entering the mines, we don't think about anything except excavating more coal to make more money."

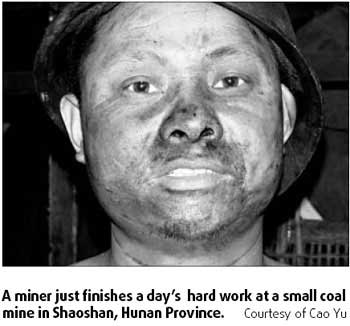

Most miners, in fact, were fully aware of the risks of working in a coal mine but believed they had no choice. A coal miner surnamed Xiao in Liuyang told the students why he chose this hazardous occupation, sharing with them a story representative of most workers' dilemmas. "Farming doesn't make much money, and sometimes it leaves us in debt," he said. "I have two sons: One studies at A deputy captain surnamed Yang said most of the workers were destitute and only wanted to make money. "Some workers are so crazy for money, they even ignore orders to leave the mine," he said. "The workers always use violence to settle conflicts, especially those involving money." At the same time, miners hoping to get the word out about the hazards they faced were willing to confide in the young visitors. "Some workers even regarded us as saviors," said Cao, now a junior. "If I promised to relay their reports to the government, they would be very outspoken." Reached by phone at "Their faces, hands and clothing were black," he recalled. He also remembered the first time he entered a mineshaft. "The tunnel was very dark and wet. Muddy water flowed around my feet, and the walls were slimy," he said. "I could only see the lamps on workers' helmets. Each lamp signified that a worker was alive." Cao's parents were concerned about his safety and wanted him to stop his research. "I am their only child, but they finally agreed with me," Cao said. Every time he conducted survey in After finishing their survey, Cao and his team spent October through December of 2006 analyzing their data. They found that supervisors felt safer than ordinary miners, workers with more education tended to feel safer, and those with more experience were less likely to risk unsafe behavior. In their final report, the students suggested a three-tier system for addressing coal mine accidents, in which they would be addressed at the level of principles, systematic construction and concrete measures.

And after finishing their report, the students honored their promises to the miners to pass on the information they'd collected. The meetings of the National People's Congress (NPC) and Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) in March presented them with the perfect opportunity. Many CPPCC and NPC members were keeping blogs to communicate with constituents via the Internet, so the students linked their report to more than 100 of these blogs and also mailed a copy of their report to the State Administration of Occupational Safety. CPPCC member Hao Ruyu, who was vice-president of Capital University of Economics and Business, praised their report, and NPC member Ye Qing, who was deputy director of Hubei Provincial Bureau of Statistics, contacted media to call attention to their research. They soon got a call from the agency saying that its director, Li Yizhong, had read the report and thanked them. Mao Shoulong, a professor of public administration at Renmin University of China in "It's an effective way for the congresses to collect information and for the students to learn about political processes," Mao said. Sounding confident and zealous over the phone, Cao said he and his companions would continue their research of coal miner's lives despite any challenge they might face. ( |

| Tools: Save | Print | E-mail | Most Read |

|

| Related Stories |