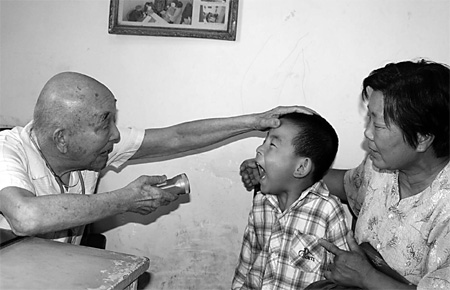

A very, very old doctor greets a few young patients and their parents inside his small private clinic. The quiet man gently smiles, nods to the children, strokes their heads and asks them to open their mouths wide as he checks their throats. The doctor is nearly deaf, but still works three hours in the morning six days a week, treating up to 20 children every day. One of them is 8-year-old Li Qingshuai, whose family had already spent more than 10,000 yuan ($1,460) in a desperate bid to treat her continuous fever.

After only three visits and paying just 60 yuan for the right medicine prescribed by the old man, the girl has quickly recovered.

Good news stories like this one happen almost every day at the doctor's clinic in Jinan, capital city of East China's Shandong province.

If you did not know him, one might never realize this frail fellow, with a strong Jinan accent, is actually, according to local media, the very last Japanese war veteran still living in China since the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggressions (1937-45).

Among the locals today Hiroshi Yamasaki is known as Dr Shan and he has lived in Jinan for some 70 years.

Yamasaki only spent six months serving in the Japanese army as a veterinarian before he escaped and after the war decided to stay in China to atone for the conduct of Japan's invaders.

"I hate wars and I couldn't bear our troop's brutality to the Chinese people," Yamasaki says.

The peace-loving doctor didn't join the invading troops willingly.

The Japanese imperial government required every family to send a son to join the army and being the youngest son in his family, the then 29-year-old, single doctor had no choice but to join the army, so his older married brother could remain with his new family.

He was first dispatched to Tianjin and soon witnessed the evil of war.

One horrific scene he recalls was witnessing a Japanese soldier strangling a Chinese baby.

Yamasaki desperately tried to save the infant but failed.

"That incident strengthened my determination to leave the army," he says.

|

|

The 101-year-old Hiroshi Yamasaki checks the throat of a boy at his clinic in Jinan, Shandong province. [China Daily] |

He deserted his troops in the middle of the night and walked east, hoping to reach the coast and find a way back to Japan. Four days later, the starving young man collapsed.

He woke up to find himself in an impoverished Chinese farmer's family. When he was strong enough to walk again, the aged couple gave him the only set of clothes they had. They were simple threads but were washed.

With the only flour they still had, the couple made a pancake for Yamasaki to take on the road.

When the old doctor recalls the couple's kindness he cannot hold back the tears.

"They knew I was Japanese but still saved my life," Yamasaki says as he weeps. "I couldn't do anything for them except bow."

More Chinese helped him along his way, and Yamasaki finally made his way to Jinan, where he found a job as a storehouse keeper at the Japanese-controlled railway, using a different name.

He secretly helped poverty-stricken Chinese workers steal the daily necessities to survive.

This eventually aroused his Japanese manager's suspicion and Yamasaki was badly beaten, but would not give away his Chinese workers.

He was not charged because of lack of evidence, but his bravery won the respect of the Chinese workers who treated him as a brother. His new friends introduced him to a Chinese woman who later became his wife.

Yamasaki settled down and opened a clinic and the couple lived a very humble life as he often treated poor patients without charge.

After the founding of New China in 1949, he heard a radio broadcast from Chairman Mao Zedong who welcomed all friendly foreigners to stay in China. Yamasaki says his heart was lifted.

He found a job in a public hospital but always passed on any salary increase opportunities to others.

The reserved doctor didn't talk much with others, including his own family. Even his daughter knew nothing about her father's past until the 1970s, after accidentally hearing Yamasaki talking to a Chinese man whom he helped 40 years ago.

Despite his humanitarian efforts, the quiet old man can never forget the Chinese people's suffering caused by Japanese invaders.

In 1976, four years after China and Japan normalized diplomatic relations, Yamasaki went back to Japan for the first time, after being away for more than 40 years.

Although his overjoyed Japanese family found a position for him in a local hospital, he told them China had become his home.

"I have lived in China for more years than in Japan, I must go back to China," he told them.

That year, when Yamasaki heard his hometown in Japan Shuku Takimoto was seeking to establish a friendship city relationship with Jinan, he returned to China ahead of schedule to help make the plan a success.

He wrote to then Japanese Prime Minister Nakasone Yasuhiro about the issue and received his handwritten reply.

With his contribution, the two cities became friendship cities in 1983 and the government of Shuku Takimoto sent him a thank you note.

"This is the only good thing I have done during my life," Yamasaki says smiling.

Actually, he has done more than he says. The selfless doctor donated books and medical equipment he bought in Japan to a library and a hospital in Jinan but didn't bring anything from Japan for his family.

He believes that the best way to make up for the guilt caused by the Japanese invasion is to "do more good things for the Chinese".

Through his personal atonement, he has won the hearts of patients. Some families have even visited him for generations.

Every year, Yamasaki donates his pension given by the Japanese government to Chinese in need.

He helps Chinese students study Japanese without charge and has cleaned the public space of his apartment building for more than 20 years.

Due to his old age, the frail doctor has started to lose his memory, and most of his Japanese relatives have passed away.

Fewer and fewer people know about Yamasaki's past, but he never forgets to "atone for guilt".

The Chinese Green Card holder even signed a form to have his body donated to science when he dies, mapping out his one last goal.

"By donating my body, I won't feel bored in the future because I know I can serve the people after my death," he says.

(China Daily July 7, 2009)