It's 1972 and a man rides his bicycle down a Beijing street, takes his hands off the handlebars and starts practicing tai chi. In another scene, on another day, in a Henan province village, a group of primary school students read their textbooks out loud, with blank expressions, as if they do not understand the characters.

To most Chinese people today the images seem innocent enough, but when the late Italian director Michelangelo Antonioni (1912-2007) released his documentary film Chung Kuo (China) these and similar scenes caused an intense political reaction.

According to an editorial in the People's Daily in 1974, Antonioni had a hidden agenda when he filmed people sitting in teahouses, an old woman's bound feet, or people blowing their noses and going to the latrine.

|

|

|

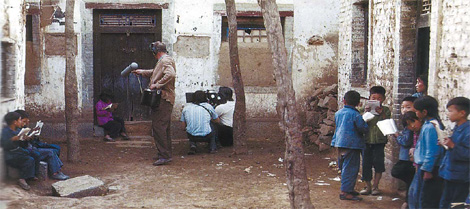

Michelangelo Antonioni and his crew filming in a Henan province village for his documentary Chung Kuo in 1972. [China Daily] |

"This 3.5-hour-long film does not reflect new things, the new spirit and face of our great Motherland, but lumps together a large number of viciously distorted shots to attack Chinese leaders, smear socialist New China, slander China's Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution and insult the Chinese people. Any Chinese person with national pride cannot but be greatly angered by seeing this film," says the editorial, titled A Vicious Motive, Despicable Tricks - A Criticism of M. Antonioni's Anti-China Film, China.

To a new generation of Chinese these criticisms seem excessive.

"When I watched the film, I didn't feel the shots were meant to damage China's image," says Ning Biaoxue, a magazine editor from Guangzhou, who was born in 1980. "To me that was the reality of China at that time. I think the film even beautified China to some degree as many scenes were shot by arrangement with the Chinese government - but that was also a reality."

Ning is interested in foreign documentary films about China because of the different perspectives they offer. He cites Dutch director Joris Ivens' How Yukong Moved the Mountain, as another example.

"To some degree my status is like theirs. As foreigners, China was unknown to them, while China in the early 1980s and before is also unfamiliar to me," he says. "The bewilderment of Antonioni is also my bewilderment: Why were Chinese people and society like that?"

In the eyes of 43-year-old Chinese documentary filmmaker Liu Haiping, Antonioni has left a great legacy with Chung Kuo, which presented China in a way that is neutral and human.

|

|

|

Italian film director Michelangelo Antonioni called himself a voyager who recorded what a voyager saw, for his 1972 documentary. [courtesy of Liu Haiping] |

"Chung Kuo impressed me so much that I decided to make a film about Antonioni, after I had seen an excerpt of just a few minutes," he says.

Since 2004, Liu has been filming China Is Far AwayAntonioni and China, for which he interviewed Antonioni at his home in Rome, as well as ordinary Chinese people.

A shortened version of Liu's film has been shown on CCTV, and the complete version was recently screened at the Broadband International Cineplex, in Shanghai.

"The enthusiasm of the audience shows a growing interest among Chinese people in Antonioni's Chung Kuo, which tracked a special period in Chinese history," Liu says.

When Antonioni was shooting Chung Kuo, China had been practically closed to the outside world for more than two decades. The situation was about to change, as China established formal diplomatic relations with Italy in 1970, and became a member of the United Nations the next year. In 1972, United States President Richard Nixon visited China.

"At that time, the 'cultural revolution' (1966-76) had already been going on for quite some years. Many people were tired of political conflicts and longed for normality," says Luo Jinbiao, who was involved in the arrangements for Antonioni's trip to China. At the time, 1972, he was an attach in the cultural section of the Chinese Embassy in Rome.

"Our invitation to Antonioni to make a documentary about China was an attempt, in the cultural sphere, to open up to the world."

In July 1971, Radiotelevisione Italiana made a request to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of China to shoot a documentary film in China, with Antonioni as the director. About 10 months later the request was granted and seven days after this, on May 13, 1972, Antonioni arrived in China with his crew.

In the following five weeks he shot footage in Beijing, Shanghai, Nanjing and Suzhou in Jiangsu province, and Linxian county (today's Linzhou) in Henan province - an itinerary set by the Chinese government.

"In seeking out the face of this new society I followed my natural tendency to concentrate on individuals, and to show the new man, rather than the political and social structures which the Chinese revolution created. These five weeks permitted only a quick glance: As a voyager I saw things with a voyager's eye," Antonioni was quoted as saying after the trip.

Chen Donglin, a researcher with the Institute of Contemporary China Studies, says Jiang Qing, Mao Zedong's wife and in power at that time, was unhappy with the film. Antonioni became a target in the then ongoing "Criticize Lin (Biao), Criticize Confucius Campaign".

Starting with the People's Daily editorial, the movement to denounce Chung Kuo lasted nearly a year, though the majority of Chinese never saw the film. A 200-page critique of Chung Kuo was published in 1974.

Chinese diplomats in Italy who were involved in preparatory work for Antonioni's trip to China were recalled, including Luo and the then ambassador Shen Ping. For months they were forced to attend a study group, denounce the film and write self-criticisms.

Antonioni's shots of the Yangtze River bridge in Nanjing, for example, were criticized for making "this magnificent modern bridge appear crooked and tottering".

Antonioni was aware of the attacks and a number of foreign governments were pressed not to screen the film. In response, he said: "The vulgar language of their accusations really hurts me".

"If I had a chance to see Antonioni again, I would have said sorry to him," says Luo. "He was wrongly attacked by people who had political aims."

In November 2004, an academic retrospective of Antonioni at the Beijing Film Academy publicly screened Chung Kuo in China for the first time, 32 years after the film was made. A few years previously the film could be seen on the Internet, with Chinese subtitles translated by volunteers. The DVD was only officially released in Italy in November 2007, four months after Antonioni passed away.

His death was widely reported by Chinese media that mentioned Chung Kuo, arousing further interest in the film in China. Some elderly Chinese, however, still cannot accept the film.

For instance, in an article that was published by the Beijing Evening News earlier this month, Ren Yuan, a 72-year-old professor with the Communication University of China, wrote: "(Chung Kuo) not only failed to present China and its people truthfully, but also harmed Chinese people's dignity".

But this is an isolated case and filmmaker Liu believes the Chinese government should also buy the footage that Antonioni left on the cutting floor, as it is a valuable record of Chinese history.

"As a leftist who was friendly with Red China, Antonioni made a 'pink' film about China," says Cui Weiping, a professor of film criticism with the Beijing Film Academy. "It not only provides rare footage of China in the 1970s, but can also serve as a case study of Chinese diplomacy at that time."

(China Daily August 27, 2009)