By Roseanne Gerin

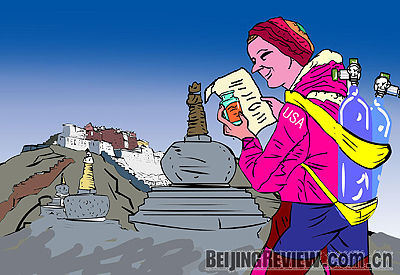

The first order of business for most travelers to China's Tibet Autonomous Region is what to do to prevent the onset of altitude sickness. The region isn't called "The Roof of the World" for nothing. It lies on a plateau that is the highest on the planet with an average elevation of more than 4,000 meters. Lhasa, the regional capital and starting point for most trips, is 3,650 meters above sea level.

My drug of choice was Acetazolamide, also known as Diamox. I took one 125-mg tablet twice a day in the morning and evening for four days-one day before my departure and during the first three days of the trip. The bottle contained several warning stickers: may impair ability to drive a motor vehicle; may cause drowsiness or dizziness; do not take aspirin or a product containing aspirin without the knowledge or consent of your physician; and avoid prolonged or excessive exposure to direct and/or artificial sunlight while taking this medicine-the last of which was very hard to do considering Tibet's intense sunshine.

Before heading off to the southern part of the region for the weeklong National Day holiday in early October, I sought additional advice from people who had traveled there in case the prescription medicine failed to do the job. I didn't want to take a chance on re-experiencing some of the high altitude effects that I had a year earlier on a trip to the mountainous area of west China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. During a few hours' stop for lunch and camel rides at Karakul Lake, a glacial lake that lies 3,600 meters above sea level near the Tajikistani border, I developed a serious pressure headache, had difficulty speaking and bit my tongue when I tried to talk.

A Canadian acquaintance who had lived in Beijing for a few years and traveled far and wide in China suggested that I drink four liters of water a day in Tibet. She received this advice from an American mountain climber she met at the base of Mount Qomolangma (Everest) a few years back. The downside: "There was an awful lot of peeing in them there barley fields," she wrote to me in an e-mail from Toronto.

Upon arriving in Lhasa, our local guide, a 29-year-old Tibetan who went by the English name Jane, suggested avoiding all medications and canisters of oxygen, which she said worked well only for sudden elevations at short intervals. Instead, she recommended lots of water, plenty of rest and no activity on the first day. Unfortunately, the water-and-rest prescription failed to do the trick for most people in our group.

Sara from the U.S. state of New Jersey became physically ill on the hour-long drive from the airport into Lhasa, more so from the strong heat and blinding sunlight. Her nausea lasted throughout the evening and continued the next day before gradually wearing off.

Talk of altitude sickness symptoms and possible preventives was prevalent throughout most of the seven-day trip. Monique, originally from Montreal, had been advised by her Chinese work colleagues in Shanghai not to wash her hair to avoid altitude sickness. They had tried this when they traveled to Tibet on a four-day corporate team-building trip. Monique did not follow their advice and washed her hair on the second day. Jane added that some Chinese also avoid showering to avoid altitude sickness. But no one gave this equally questionable precaution a second thought.

Our hotel in Lhasa thoughtfully provided plastic canisters of oxygen for 40 yuan ($5.8) each in our rooms along with 40-yuan boxes of red tablets containing Tibetan rhodiola, a herb that grows in the region's mountains and is said to increase physical and mental stamina and boost the immune system. The box said it was best to take two capsules twice a day at the start of one's exposure to high altitudes. No one tried them, although an American from Texas took some similar-looking blue herbal pills that he bought from a Chinese pharmacy in Beijing. Nevertheless, he still had several days of headaches and queasiness.

Some members of the group took no medicine at all. Di from Australia said she could not take Acetazolamide, because she was allergic to sulfa medications. As a result, she suffered from "altitude giddiness" during most of the trip.

The altitude did affect my year-round sinus and allergy conditions. Despite taking an over-the-counter allergy medication and using a prescription nasal spray during the trip, my nose was stuffy most nights, and my nostrils were slightly bloody, especially in the morning. Yet, with the Acetazolamide I was able to avoid the other maladies my fellow travelers complained of-hangover-like headaches, heart palpitations, general nausea and a lack of appetite. Avoiding alcohol (except for a few glasses of beer), drinking a cup of ginseng tea in the evening and walking slower than usual when ascending high places on hillsides, such as Potala Palace in Lhasa and the Dzong Fortress in Gyangze, also helped. I also chewed peppermint chicklets to ward off a dry throat and an upset tummy.

Jane said it was normal for visitors to become acclimated after three or four days once they suffered through all the headaches and nausea, and that by the time they left six or seven days later, they had no problems. And so it was with all of us as we boarded our planes back to Beijing and Shanghai.

The writer is an American who lives and works in Beijing

(Beijing Review December 25, 2008)