Wake-up call for a non-stop world

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail China Daily, November 25, 2019

E-mail China Daily, November 25, 2019

There are more smartphones in the world than there are people and the device's proliferation is outpacing the growth of the human population, according to the United Nations' International Telecommunications Union. The inability to switch off has become one of the most important and pressing issues of our time. It has been estimated that, in Britain, people check their smartphones every 12 minutes, when taken as an average over a 24-hour period.

Netflix CEO Reed Hastings named the company's biggest competitor: not Amazon or YouTube, but sleep. He explained, "We're competing with sleep, on the margin. And so, it's a very large pool of time." There's so much competition, it can seem as if there are not enough hours in a day to actually stop and sleep. And when we're sleep-deprived, our ability to pay attention reduces drastically and our productivity drops, creating new economies around self-tracking devices and other sleep aids.

So great is the problem that it's considered a public health epidemic. As of last month, 5.13 billion people in the world owned mobile devices – 66.5% of the world's population. And it's growing. Generation Z (people born between the mid-1990s and the early 2000s) is the demographic that owns the most smartphones; some 98% own a smartphone and 52% claim it is their most valuable asset.

It's estimated that an average person spends two hours and 52 minutes per day on their mobile device. About 22% of users check their phone every five minutes. So it's not just an epidemic – it's also an addiction.

In London until February 23, 2020, Somerset House's latest exhibition 24/7, inspired by the book 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep by essayist Jonathan Carey, takes visitors on a journey through five zones based on the tensions of life in a non-stop world. New technologies have blurred the boundaries between day and night, activity and rest, the human and the machine, work and leisure, and the individual and the collective.

Interestingly, the beginnings of this 24/7 culture can be traced back to the Industrial Revolution, with workers being rostered around the clock. The distinction between day and night effectively eroded, disrupting the body's natural rhythms – and that has intensified during the Information Age.

Early examples of the phenomena include Joseph Wright of Derby's Arkwright's Cotton Mills by Night (1782), in which he painted a Derbyshire cotton mill owned by Richard Arkwright, inventor of the modern factory. It is believed to be one of the earliest depictions of British 24/7 culture, with workers made to do shifts around the clock.

It's a reminder of how the split between business and leisure time has blurred, with more homeworkers and more coffee shops becoming working hubs than ever before. Once touted as the future of employment, the current gig economy has proven a honey trap for some; despite the illusion of greater flexibility and freedom away from the office, the reality can be quite precarious, requiring more time for work and less for rest and relaxation. It often leaves individuals in isolation, rather than part of a collective who can convene to champion workers' rights.

Roman Signer's Bett (1996) shows a film of the Swiss artist asleep on his bed as a remote-controlled helicopter frenetically swoops and hovers above his head. Tatsuo Miyajima's Life Palace (Tea Room) (2013) is a meditative isolation chamber, through which the Japanese artist invites people to climb and, within the blue glow of blinking LED numbers, drink in the passage of time.

Iain Forsyth and Jane Pollard's Somnoproxy (2019) is a futuristic story in which someone offers services to sleep on behalf of wealthy executives who are too busy and stressed to get any sleep for themselves. Visitors are invited to lie down in a large hotel bedroom and experience this sonic escape from reality.

British artist Mat Collishaw's The Machine Zone 00-01 (2019) sees six animatronic birds move inside glass boxes, exploring the idea of random reward. The concept highlights the algorithms driving social media interactions and has been linked to our likelihood to become addicted to them.

And Australian artist Tega Brain reveals the hacks to cheat fitness-tracking devices such as Fitbit in her project Unfit Bits (2015). The simple DIY strategies trick wearable technologies into believing that people have engaged in more physical activity than they have, helping to produce data to qualify them for incentives from employers or insurers, even if they can't afford a high-exercise lifestyle. Unfit Bits' hacks highlight the unreliability of such data streams – ones on which we seem to increasingly depend.

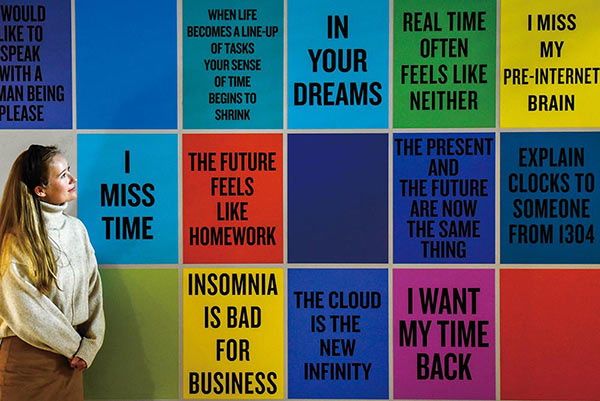

Punctuating the entire exhibit are author Douglas Coupland's provocative Slogans for the 21st Century (2011–present), boldly printed on brightly colored backgrounds that echo the form and color of standardised paper found globally in office environments and Instagram posts. There are 148 all-caps proclamations – such as "Being Middle Class Was Fun", "Automated Governments Are Inevitable" and "I Miss My Pre-Internet Brain" – that surround viewers and speak emphatically to contemporary citizens, indicating how much society has changed within one generation and hinting at more dramatic changes to come.

Go to Forum >>0 Comment(s)