Two left-behind generations in 3 decades

- By Wu Jin

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail China.org.cn, March 30, 2016

E-mail China.org.cn, March 30, 2016

|

|

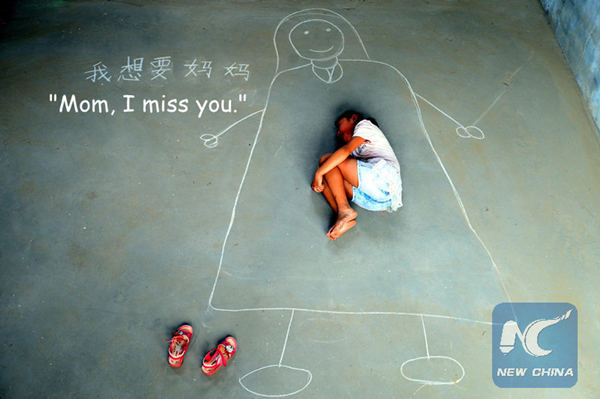

A girl sleeps in her mom's arms painted on the ground in Nanguan Village of Chiping County, east China's Shandong Province, July 25, 2015. [File photo/Xinhua] |

Loneliness, as a result of constant separation from their parents, has destroyed the confidence and happiness of left-behind children dwelling in far-flung villages throughout China.

Totaling more than 61 million, the left-behind children in rural China have imposed a grim challenge in view of their fragile psychological conditions resulting from a lack of parental love.

A string of data reflecting the accidents of the left-behind children can help verify the case.

In 2014, about 49.2 percent of left-behind children suffered accidental injuries. From 2014 to 2015, 55.2 percent of the 192 cases of the sexual harassment of girls exposed by media outlets were related to the left-behind children. In July of 2015, the first issuance of a white paper revealing the hearts and minds of left-behind children in China disclosed that roughly 10 million children cannot see their parents year round.

These stagnant conditions of rural children in China have lasted for two generations.

Invisible walls preventing the free-flow of rural and urban human resources collapsed in 1984 when a circular issued by the central government lifted up the restriction of rural residents to join in urban life.

As a result, the country has seen a massive migration of the young labor force moving from the villages to big cities. In 1989, the outsourced labor force grew from less than 2 million to 30 million, an immense increase causing the loss of the young labor force in most desolate villages and leaving behind a younger generation living without love and care from their parents.

Huang Xiangjie has grown up in a rural village called Laosiyan in Hunan Province. With the successful conservation of its original looks, featuring a long precipitous slate alley, an old tree whose roots extend deeply to the rocky mountain at the entrance of the village and the dilapidated houses passed down from several generations earlier, the village has fallen into silence during the past few years as half of its labor resources, mostly composed of young people, have moved to cities for temporary or permanent jobs.

Huang was born to the village and left behind with her elder sister and younger brother by her parents who headed to cities for job opportunities when she was barely two years old.

"Family conditions in the village at that time were indicative of poverty," said Duan Chengrong, a professor focusing on the research of rural villages from Renmin University. He recalled an investigation regarding rural villages headed by his mentor when he was still a postgraduate in 1984, a year which witnessed a great impulse of young people to find jobs in cities.

Huang Yunsheng, father of Huang, still remembers that the family was extremely poor at the time -- two years from the adoption of the Household Responsibility System [an agriculture production system launched in the early 1980s, which allowed households to contract land, machinery and other facilities from collective organizations] -- when they hardly had anything to cook, had they taken a break from farming.

However, upon her father's leave, a miserable memory of the loss of this parental presence tortured the heart of Huang, who led a lonely childhood when she met her father only once a year during the Spring Festival and her mother at intervals lasting several years.

After Huang grew up, she became a volunteer teacher at a kindergarten in her hometown after she obtained a bachelor's diploma from her university. She resolved to leave the post eventually, as the villagers in her hometown laughed at her return, saying she must have not been able to secure a job in one of China's big cities.

After a year, she hardly had the spirit to leave as she found the trauma left by the absence of the children's parents has forged a close tie between her and her students who are undergoing a life similar to that of her childhood.

"I don't want to let those children be neglected again," Huang said.

According to an evaluation report on rural education from 2000 to 2010, 63 primary schools, 30 educational branches and three secondary schools disappeared each day on average in rural China which aborted the plan to spread primary education in each village.

As a result, the average distance between home and school for students in desolated villages has become roughly 1.6 to four kilometers on average, which has caused a huge tide of dropouts.

Many children left behind by their parents have to shoulder the responsibility of taking care of their senile grandparents instead of being cared for and educated by their elders, recalled Zhang from a program led by one of his undergraduate students in the student's hometown.

In February of 2016, the State Council issued an opinion which has for the first time sketched out a top-design framework for left-behind children. For the first time, the opinion also regulates which department should be held accountable for the left-behind children. The Ministry of Civil Affairs will conduct an investigation, together with the ministries of public security and education, concerning China's left-behind children until the end of this July.

By 2020, according to the opinion, the number of left-behind children should be greatly reduced under the lead of the Ministry of Civil Affairs.

Go to Forum >>0 Comment(s)