British capitalism: A rentier economy

- By Heiko Khoo and Michael Robert

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail China.org.cn, May 31, 2018

E-mail China.org.cn, May 31, 2018

The U.K. economy slowed to almost a standstill in the first quarter of 2018, growing by just 0.1 percent in real terms; the lowest growth rate since 2012. There was a meagre rise in household spending and business investment shrank.

The government and the Bank of England blamed this year's bad weather. Whilst poor weather hit some parts of the construction industry and the retail sector, the official statistical agency, ONS, says "its overall impact was limited" and points to an underlying slowdown in the growth of consumer spending.

U.K. growth is slower than the leading G7 capitalist economies, and its productivity growth has fallen to under 1 percent a year. Britain's output per hour of work grew at an annual pace of 2.2 percent a year before the 2008-09 economic crisis, but since 2007 that rate has dropped to 0.2 percent. The U.K.'s national income would be 20 percent higher than it is today had previous trends continued.

The ONS points to the U.K.'s "productivity puzzle" – the difference between post-downturn productivity performance and the pre-downturn trend. In the U.K. this was 15.6 percent in 2016, around double the average of 8.7 percent across the rest of the G7, only Italy performed worse.

The U.K. economy is not suffering from bad weather or ''uncertainty'' caused by Brexit, but from deep underlying structural problems. British capitalism has become a "rentier" economy, one in which surplus value increasingly comes from extracting "rents" and financial profits from the productive sectors in other parts of the world.

New studies on the reasons for Britain's poor productivity record indicate that the failure lies in the heart of British capital, its big multinational exporting companies. A detailed analysis by the Economic Statistics Centre of Excellence published this month shows that three-fifths of the drop in productivity growth stems from sectors representing only a fifth of output, including finance, utilities, pharmaceuticals, computing and professional services.

The Bank of England made a similar analysis and found that the nation's top companies have become the slackers. According to its research, the most productive groups are "failing to improve on each other at the same rate as their predecessors did." The top companies improved their productivity more than the small companies but at a slower pace than before the Great Recession; and so overall productivity growth slowed and fell further behind other major capitalist economies.

It is the most successful companies that drive success in the U.K., and they are normally those with highly skilled employees, and which are exposed to international competition through exports. Paul Swinney, the head of policy and research at the Centre for Cities, says the "idea that if only we can make the bottom 20 percent of businesses more productive . . . is a bit of a red herring."

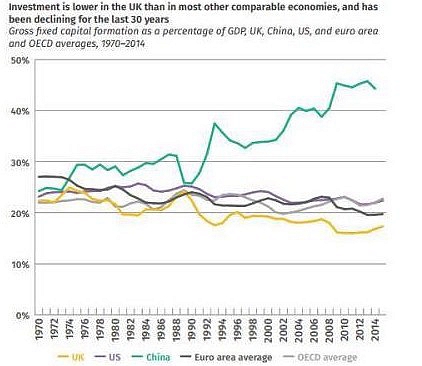

Why is productivity growth so poor in Britain, especially among the key big British multinationals? The answer is clear: reduced business investment. The latest business investment figure for Q1 2018 shows an absolute fall in investment. In fact total U.K. investment to GDP is lower than most comparable capitalist economies and has declined for the last 30 years.

World Bank (2016) Gross Fixed Capital formation (% GDP)

Most mainstream economic studies accept that the U.K.'s poor productivity record, particularly since the end of the Great Recession, is due to low investment in key productive sectors by key large companies – but they don't explain why.

The core question remains profitability i.e., profits per stock of capital invested. The profitability of the productive sectors of the British economy remains low compared to before the Great Recession. In fact, despite the credit boom of the early 2000s and the recovery since the Great Recession, profitability remains below its 1997 peak. As a result, British capital is invested in financial assets, hoarded in tax havens, or invested abroad rather than in the U.K.

While German capitalism maintains its manufacturing sectors through new technology, investment and exports (and relocation to the east), British capitalism favored finance and related services over production. The neo-liberal policies pursued since the 1980s, and global competitive pressure on the industrial and manufacturing sectors accelerated this tendency amongst British investors.

Thus, rather than boost labor productivity through investment in new technology, British capital concocts schemes to conjure up money from money through the financial sector. This is the hallmark of a "rentier" economy.

Heiko Khoo is a columnist with China.org.cn. For more information please visit:http://china.org.cn/opinion/heikokhoo.htm

Opinion articles reflect the views of their authors, not necessarily those of China.org.cn.

Go to Forum >>0 Comment(s)