Steering swordplay

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail China Daily, January 11, 2013

E-mail China Daily, January 11, 2013

Wuxia classics are the glory of Chinese cinema and their heroes are very much like the Robin Hoods of the West. But new wuxia productions are often mediocre in concept and suggests that it will take a new mindset before a breakthrough can be achieved.

By most accounts, wuxia is the only film genre invented by Chinese-language cinema. You know it when you see it, but it is not quite easy to define. Wuxia is commonly known as martial arts or kung fu. Both these terms - the second coined in Hong Kong and spread to the rest of the country - describe the action, not the spirit. In that narrow sense, it is a kind of Chinese action film, usually set in ancient times. The Chinese word wuxia contains wu, meaning "martial" or "military" and referring to the action, and xia, roughly translated as "chivalry". As we all know, Chinese "chivalry" is very different from the Western code of conduct associated with the medieval institute of knighthood. For one thing, Lancelot's courting of Queen Guinevere has never been adapted into a Chinese play or film.

A typical wuxia movie combines the element of action with a moral code in a ratio the filmmaker sees fit. If you have 100 percent wu and no xia, you have a video of a martial-arts competition. If it's all xia without any wu, then it would be a courtroom drama or some other kind of drama.

Is it for real?

There is a myth about wuxia action: Some would have you believe it's realistic while others claim it's all make-believe. You don't really need to be a martial artist to know the difference.

Many of the moves used in movies are based on real martial arts of various schools, but are no doubt exaggerated for dramatic purposes. As many Hong Kong filmmakers readily admit in media interviews, they are often more influenced by the dance sequences of Hollywood musicals of the 1950s-60s than by a particular method of Chinese martial arts.

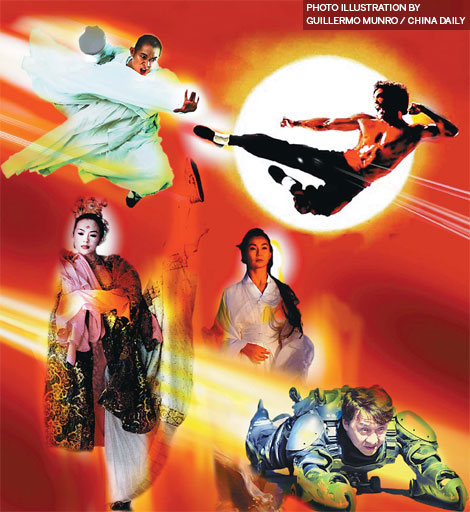

The fact that three of Chinese cinema's greatest martial artists - Bruce Lee, Jackie Chan and Jet Li - are all solidly trained in real martial arts rather than movie exhibitions may give the wrong impression that what you see on the screen is the real McCoy.

The 1993 biopic Dragon: The Bruce Lee Story has a scene that depicts Lee finishing a complicated set of moves with no regard to camera angles and other film techniques for fragmented shooting. (Of course, this must have been apocryphal because Lee was a child actor before he became a kung fu legend and surely knew the requirements of filming.)

Movie action is designed to not only look good but also sound good. The ubiquitous punching sound for physical contact is obviously enhanced. What kind of body will yield such a slightly hollow and wildly amplified sound when hit - other than a puffed-up pillow?

The most fascinating thing about martial arts as exhibited on the Chinese screen is the tendency to venture into the fantasyland.

Hollywood action flicks are not realistic in their action scenes either, but they usually adhere to a logic that makes sense of the action. If the action is humanly impossible, Hollywood will provide a "scientific" justification, so that Spiderman, Batman or Superman will function without audiences collectively scratching their heads.

In a Chinese movie, a hero may catch flying arrows with bare hands, but the audience is rarely told how this craft became plausible.

Chinese wuxia films fly in and out of the fantasy realm as if it's taken for granted. However, audience reception depends on how dexterously the film treats such details. How much the action scenes are heightened, so to speak, should have an inner logic.

In Ang Lee's Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, flying starts with fast running - so fast the feet on the roof are increasingly floating on thin air. Only in the second half does full-force flying take place.

Suppose the two scenes are reversed. I can guarantee the second one will not have the impact it was designed for. In a sense, flying is the ultimate test for wuxia movies that depict supernatural skills. If the audience laughs, it means it is rendered ridiculous; if there is a gasp of wow, it has sent the heart palpitating.

In a way, the best flying I have seen is still the bike-riding scene in Spielberg's E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial.

Peter Chan's Wu Xia - a.k.a. Swordsmen or Dragon - is revolutionary in that it attempts to rationalize all the Herculean tricks with Sherlock Holmes-like precision. To look at it from a cultural perspective, he gave himself the daunting task of fusing Western science with Eastern metaphysics. The computer-generated imagery of the human organs bearing the brunt of a punch is an honorable effort at explaining the unexplainable.

Just as traditional Chinese medicine is for the converted, screen kung fu is built on a premise that it will involve actions not humanly possible. What Chan did was tantamount to Pixar using all 23 million balloons that were technically needed to lift the house in Up. It would be like a tether that binds a flight of fancy.

The real challenge that faces Chinese wuxia is new human movements that are different from the tried-and-true. The martial-arts world needs its own equivalent of Isadora Duncan, who revolutionized the body language of ballet. The current crop of choreographers, most of them Hong Kong raised, have done so many movies that it is understandable they are running out of inspiration.

Fighting for what?

Martial artists fight for a cause. There are arguments that this is where the Chinese spirit shines. In my mind, the principles embodied by these brave souls are strikingly similar to those in other genres, especially the Hollywood western.

Naturally, Chinese heroes come in all stripes and may have faith in any of the religions and sects popular in China, such as Taoism, Buddhism, Confucianism or a blend of these and local variants. Redressing wrongs and seeking justice are frequent motives.

Most wuxia heroes have humble upbringings, which endear them to the masses but alienate them from the literati. They are rebellious by nature, which runs against the official orthodoxy of Confucianism. The literary genre of wuxia was often banned by the powers-that-be, chiefly because it tends to inspire a collective sense of disobedience.

Wuxia heroes place their sympathies with the weak and downtrodden. Their stories often start with a tragedy that remind them of the vulnerability and agonies of being powerless, corporal, mental or official. Act One usually ends with them leaving their homeland in search of more martial skills. Act Two portrays them as wanderers, who encounter mysterious masters and rigorously learn the tricks that will eventually empower them in their fight with the representatives of evil.

Sometimes, xia does not have a vested interest in the good-vs-evil standoff. He or she happens to come by, a la a cowboy sauntering into town, and witness an act of injustice. This dissociation from the crowds makes them pure bystanders whose righteousness determines the final result.

While the search for an English equivalent for xia is futile, I feel "maverick" may be the closest in capturing the strong sense of independence often embodied by this loner type.

In China, the family is the basic societal unit. When the emperor punishes an underling, it is not the death sentence that is the harshest. His whole family could be put to death - including even distant relatives. This kind of guilt by family connection deters most people from standing up for justice. It has to be a whole village or even larger assembly that gets organized and together faces the ultimate consequence of insurgence.

That makes the odd person who stands up to authorities a target of secret admiration - and probably of public ridicule if it happens in real life. These figures are often detached from the web of family associations. In fiction, they are usually portrayed as having no past, which, if you think of it, is the Chinese equivalent of having a mysterious past or a double identity, such as Bruce Wayne-cum-Batman.

In terms of existing religion, xia tends to gravitate toward Taoism rather than Confucianism. Taoism advocates freedom from worldly pursuits and disdains the lure of officialdom, but Confucian promoters seek to work from within the establishment to address social ills. In reality, Taoists tend to excel in art and literature, and the wuxia canon imposes a physical prowess onto them.

What's in the future?

Visually, wuxia heroes often wear white flowing robes, exuding an ethereal charisma that suggests out-of-this-world qualities. They are rarely imposing in stature, but have lithe and sinewy physique capable of superhuman agility. Herein lies the Chinese aesthetics of physical beauty.

As the spirit of xia continues to inspire, it is time new variations took shape to breathe new life into the genre. For example, can a nerd be a martial artist who saves the world?

He can be a bookworm by day and Superman on call, with a wardrobe and hairstyle change to go along. Or, can a Chinese xia come from a wealthy background, as Bruce Wayne did, and equip himself with not only a special outfit but a unique vehicle to boot?

In the 1960s, authors like Louis Cha and Liang Yusheng updated the literary genre by infusing it with high historical and literary values, spawning endless film and television adaptations that see no end even today. So far, the visual medium is still miles behind the literary origins in both imagination and execution, even with the aid of computer imagery.

There is no shortage of film masterpieces of the wuxia genre. If you scrutinize them, you'll find each pushed the envelope a little bit by adding something new to the genre and extending its boundary of expression.

Since Chinese audiences, by and large, are conservative in outlook and do not take too well to efforts of experimentation, even such milestones as Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon were not well received at home in their initial run.

A new landmark in wuxia cinema may go in one of several directions. But it will take someone who is able to think out of the box.

Go to Forum >>0 Comment(s)