Ask Helen Lai for an explanation of the relationship between ancient scripts and contemporary writing. The acclaimed choreographer of the Hong Kong City Contemporary Dance Company (CCDC) was inspired by both to create HerStory, which premiered at the Hong Kong Cultural Center Studio Theater, last month.

The ancient script in this case was "nushu", literally "women's writing". It was a unique form of written language developed 400 years ago by the women of Jiangyong County, Hunan province, to communicate in secret. Lai learned about it 10 years ago in a Chinese magazine article.

"I was intrigued and instantly thought of creating a dance about it," Lai says. "But the topic was typically Chinese, involving an ancient tradition and people; while classical or folk dance doesn't feature in my background. Also, due to the circumstances, 'nushu' often conveys a strong sense of being suppressed. This was not the sentiment I was interested in expressing through my work."

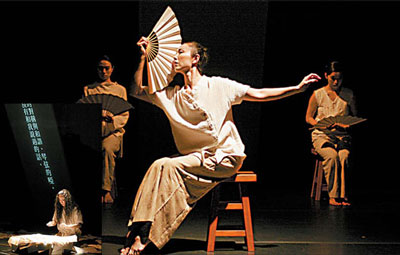

Choreographer Helen Lai's new production HerStory. (file photo: China Daily)

So the idea was dropped, and was only picked up again when Lai encountered some writings last year by contemporary local female authors, Wong Bik-san and Xi Xi.

"It was then that I realized the term 'nushu' could also mean 'women's writing' in its broader sense. In that case, it is not an arcane language, but part of a constantly expanding and evolving vocabulary for women."

This revelation allowed Lai to transcend the pages of the ancient texts and create a powerful dance about modern women searching for their own identities.

This is not the first time that Lai and her fellow choreographers at CCDC have made something decisively contemporary out of an idea that has been in existence for hundreds, or even thousands, of years. Lai's Revolutionary Pekinese Opera was created 10 years ago, for Hong Kong's handover to China.

"The title was originally given by a Japanese composer for his musical creation. That piece is a crazy collage mixed up with everything from Western music and revolutionary Chinese songs to radio advertisements and newscasts - in both Chinese and Japanese. The cacophony of sounds and jarring notes made my heart speed," Lai says.

"I felt this piece of music captured the prevailing mood of the Hong Kong people before the handover - anxiety mingled with fear and expectation."

"The sense of surrealism is heightened by the occasional Peking opera singing that seems to linger in the background. To me, this also served as a metaphor for the general feeling of Hongkongers toward their country - Chinese influences were always present, but at the same time distance had always existed."

Lai borrowed the music and added a visual part for the story. On stage, dancers were dressed in modern clothes, their dance steps were light and quick, but their faces were heavily made up like Peking opera singers.

"The piece had a fast tempo," Lai says. "I wanted to convey dynamism and uncertainty and also the sense of surrealism that surrounded Hong Kong before July 1, 1997."

Lai is not the only contemporary dance choreographer in Hong Kong who has been looking to the past for inspiration, including ancient texts and traditional art forms, legends and folklore.

Willy Tsao, founder and artistic director of CCDC, is a master of reinventing old ideas. A quick glance at his portfolio reveals a large number of works that have mined Chinese history and culture. These include Tales from the Middle Kingdom, China Wind China Fire, Sexing Three Millennia, 365 Ways of Doing and Undoing Orientalism, and Warrior Lanling.

Tsao has developed his own theories about the relationship between a contemporary dance piece and the source of its inspiration.

"I am not interested in retelling an old tale on stage - a theater director could do it better. Instead, when people go to see my works, all they see is 'me', not history," Tsao says.

"History is only the starting point. It allows me to communicate with the audience my feelings and reflections. After all, I grew up in a modern era with my own cultural luggage. It's virtually impossible for me to shut myself inside a room in the Forbidden City and think the way people did hundreds of years ago."

An example of this is Tsao's latest work Warrior Lanling. The lead character is an ancient general from 1,500 years ago. He was said to have a face as fair as a woman. But to intimidate his enemies on the battlefield he always wore a fearsome mask.

Tsao thought this mask was an appropriate metaphor for the guises behind which modern people hide themselves. He made a dance based on the idea and titled it Of Masquerade.

"We wear different masks in different places, and put on different ones for different people. Masks represent how we want ourselves to be perceived. But at the same time, we are confounded, or even scared, by the masks worn by other people."

"The fact that I'm not bounded by history means that I can do whatever I want when dealing with it."

That includes questioning, satirizing, or even undermining it, as Tsao had done in one of his most acclaimed works 365 Ways of Doing and Undoing Orientalism.

Throughout the one-and-a-half-hour show, audiences are presented with a bewildering array of Chinese cultural symbols from Peking opera, to kungfu kicks and dragon dances.

But in each scenario, there is a shock. The different body parts of the dragon are suddenly torn asunder and used to mop the floor; or a cheongsam-wearing girl stops playing the zither and starts playing golf with the instrument.

"What is orientalism after all? To me, it is like cultural imperialism - the only way the West wants to perceive the East. Sometimes it's sad to see that Chinese choreographers are complicit in this and give Western audiences what they want, to reinforce their preconceptions."

"I want to contradict all this, in an indirect way. I give them what they want, but not exactly what they want," Tsao says.

"China has changed, it's impossible for its art not to change. As a matter of fact, when a country is not strong enough and its artists not confident enough, they tend to cling to certain cultural symbols as a way of expressing unity and a common identity. China has passed that stage, which is not to say that our cultural legacy is unimportant, but rather, we should build on it instead of hiding behind it."

(China Daily January 22, 2008)